Posts Tagged ‘amateurradio.com’

Morsemail and LCWO.net

Morsemail and LCWO.net

The time has come when I can’t put off learning Morse code any longer, With an interest in vintage amateur radio and the impending restoration of a Heathkit AT-1 I’m going to need to use CW sooner or later.

So I have been checking out resources for learning Morse code and stumbled across two that really intrigue me.

The first is LCWO.net, a web browser based Morse code learning tool that is usable on any internet connected computer. It is available free of charge and there is no software to install. LCWO.net keeps track of where you are in your lessons and where you need to concentrate your effort. The Koch method is the primary tool available but they also offer code group practice, callsign and plain text training modes along with a service to convert text to Morse MP3s for download and use offline.

Once you are on the way to CW proficiency and want to communicate with others you can always fire up a rig and get on the air … What if you don’t have a rig or need a confidence boost before ‘going live’?

Well, you could always send Morsemail using the Morsemail client from http://brasspounder.com:8873/.

Morsemail is, “A simple text format that encodes mark and space times to make it possible to send Morse coded messages via email” but a recently added feature allows for QSOs using a internet repeater hosted on brasspounder.com. You can use a mouse or actual key wired to the mouse or joystick buttons to send CW which can be emailed or sent through the repeater live.

Now I just have to carve out the time to sit down and use these resources!

DIY Magnetic Loop Antenna – Part 2

DIY Magnetic Loop Antenna – Part 2

Part 1 of the DIY Magnetic Loop Antenna covered mostly theory and materials so now its time to move on to designing the magnetic loop antenna (MLA).

If you have priced a commercially made MLA you’ll see prices start at $400 and keep going up, and up. If they cost so much you would think they must be difficult to build or use expensive parts, right? Well, it is certainly possible to spend more and get a higher quality MLA but a low cost MLA will still work very well.

For the purposes of this article we’ll assume that you want to build a loop to cover the 20-10M bands. I’ll run through the calculations required to build the MLA.

The required information for the MLA calculator is:

- Length of the loop

- The conductor diameter

- Frequency/s of operation

- Input power to the antenna

- We don’t really know the best length of the loop at the moment so I’ll pick 9 feet circumference as a starting point (It’ll still fit in the trunk of my car)

- Since we seem to be having better luck with sunspots now I’d like to try 10M so we’ll start with 29 Mhz as the highest frequency we’ll use.

- I have some copper pipe left over from an ice-maker install, it is 1/4 (0.25) inch in diameter.

- Input power to the loop will be 100W.

A peak voltage of 5181V will require a minimum spacing of 1.7 mm (peak voltage / breakdown voltage per mm) between the closest conductors in the capacitor. That would rule out an old air spaced variable capacitor from a vacuum tube radio but you could still use a wide spaced variable capacitor from an antenna matching unit or transmitter. A vacuum variable capacitor would be great (watch the minimum capacitance) or a home-made capacitor would also be fine provided you checked the breakdown voltage of the insulating material.

A peak voltage of 5181V will require a minimum spacing of 1.7 mm (peak voltage / breakdown voltage per mm) between the closest conductors in the capacitor. That would rule out an old air spaced variable capacitor from a vacuum tube radio but you could still use a wide spaced variable capacitor from an antenna matching unit or transmitter. A vacuum variable capacitor would be great (watch the minimum capacitance) or a home-made capacitor would also be fine provided you checked the breakdown voltage of the insulating material.  DIY Magnetic Loop Antenna – Part 1

DIY Magnetic Loop Antenna – Part 1

Do you live in a neighborhood with a restrictive antenna policy and despair of having a useful HF antenna?

Can you solder or know someone who can?

A magnetic loop antenna may be the answer and they are not as difficult to build as you might think. Like getting on the air for the first time or taking your license exam there is a certain amount of uncertainty when you first approach magnetic loop antennas, there are a few new ideas to grasp. However, thanks to other hams like Steve AA5TB there are tried and tested designs, calculators & building methods that are known to work and that you can follow.

At the heart of every radio and MLA (Magnetic Loop Antenna) is the resonant circuit. The combination of an inductor (a wire has inductance, but a coil of wire has more) and a capacitor (two conductors separated by an insulator) in a circuit will resonate or ‘ring’ at a certain frequency. Sound vibrations at a certain frequency can cause a piano string to vibrate in sympathy and a vibration of the correct radio frequency will cause a resonant circuit to electrically vibrate in sympathy.

Since there is no such thing as a free lunch, the sacrifice you make with a MLA is that it needs to be re-tuned whenever you change frequency on your transceiver. The frequency range over which it is resonant is very small, typically only a few hundred kilohertz at the most.

The materials you can get your hands on is going to decide the capabilities of your MLA. Ideally you’ll have a loop made from a conductor with very low resistance (usually copper) and a capacitor that can handle high voltages. A variable capacitor is required if you want to use your antenna on multiple frequencies but you can use or make a fixed capacitor if you operate on one frequency, for Eg PSK31.

A MLA calculator like the Excel spreadsheet from Steve AA5TB or this web page from 66pacific.com will help you to decide what size components you’ll need to make your antenna.

The four pieces of information required are:

- What frequency or frequencies do you wish to transmit on?

- How large do you want the loop to be (It should have a circumference less than 10% of the design frequency wavelength, both calculators help you figure this out)

- The diameter of your conductor (Three quarter inch (0.75 inch) copper pipe is a good start)

- How much power you want to use (The voltage across the capacitor is proportional to the input power to the MLA)

A MLA of a certain circumference will be more or less efficient based on the frequency you transmit at. It is worth changing the loop size in the calculator to get the best efficiency possible in your favorite band.

A MLA of a certain circumference will be more or less efficient based on the frequency you transmit at. It is worth changing the loop size in the calculator to get the best efficiency possible in your favorite band.  My Trusty Ol’ Heathkit HW-8

My Trusty Ol’ Heathkit HW-8

Reminiscing about my early days in ham radio, one of the things that really stands out is a gift my parents gave me 32 years ago — a Heathkit HW-8, an 80/40/20/15 meter QRP CW transceiver! It was an utter surprise to me; I never had the slightest inkling that it was coming. I was 12 years old and had never built anything like that before. How wonderfully mysterious all those parts looked as I pulled them out and set them on the dinner table!

Reminiscing about my early days in ham radio, one of the things that really stands out is a gift my parents gave me 32 years ago — a Heathkit HW-8, an 80/40/20/15 meter QRP CW transceiver! It was an utter surprise to me; I never had the slightest inkling that it was coming. I was 12 years old and had never built anything like that before. How wonderfully mysterious all those parts looked as I pulled them out and set them on the dinner table!

Looking back on it now, I realize how patient my mother was to let me take over that table in the dining room. As I recall, I worked nonstop to build the little rig and its power supply. Ten days later, on January 3, 1980, it was finally ready. My dad took a look at it and said it was ready for the “smoke test.” You can imagine how I held my breath as we plugged it in and turned it on. I was waiting for something on the circuit board to go up in a puff of smoke! Nothing exploded, so I was ready to take it into the shack and hook it up to an antenna and straight key. “Ready” is an understatement — I was so excited to get that rig on the air I was nearly bursting at the seams!

I picked up the phone and called Dr. Bernard “Bernie” Northrup, KAØDKN, a friend of mine across town, to see if he would get on the air and give me a signal report. Dr. Northrup (later NØCIE, now a silent key) was a professor at Central Baptist Theological Seminary of Minneapolis and a fellow member at Fourth Baptist Church, Minneapolis. Not long before, he had gotten his license after hearing me talk incessantly about ham radio at church (I’m afraid back then I was more interested in ham radio than spiritual things.). Anyhow, I called him (around suppertime, I see by my log!) and he graciously agreed to get on the air.

And sure enough, my HW-8 worked! After a half hour with Dr. Northrup on 15 meters I was ready for my first “real” QSO, as I thought of it. Tuning around the band, I heard ZL4KI. My heart started thumping as I prepared to call him. Could he really hear me even though I was sending with no more power than that of a small flashlight? My hand was shaking as I tapped out ZL4KI ZL4KI ZL4KI DE NØART NØART NØART KN and waited, flushed with excitement. I could hardly believe it when I heard my callsign as he came back to me! To think that the signal from this little radio, built with my own hands, was being heard 8,700 miles away in Invercargill, New Zealand! Amazing!

Other radios have come and gone, but that trusty ol’ HW-8 is still with me. As a boy I brought it with me to church camp and set it up in the lodge, tapping out CW while the other boys played games. Once on a trip to Louisville, KY I set it up on the second floor of my grandparents’ house — with a TV-twin-lead dipole my father had built — and worked a station in Poland. When I moved into my first apartment as a newlywed, I set it up with that same dipole in my (below-grade!) apartment. On a couple of memorable, crisp, autumn days, I brought it to a local park with a thermos of hot cocoa, sat down on a carpet of pine needles, and thrilled to the sound of soft static and CW.

And last summer, when I just couldn’t wait until I got my shack set up at my new QTH, I set it up on the picnic table in my backyard with an OCF dipole tossed into the trees. Even though that antenna was so low its feedpoint rested on the picnic table, I still worked both coasts on 20m with my trusty ol’ Heathkit HW-8! What a great little rig. Thanks, Mom and Dad, for giving me such a great gift!

Now I understand – Phase Locked Loops

Now I understand – Phase Locked Loops

Every now and then I come across great books or videos that explain a concept in such a way that it becomes immediately obvious what is going on. I’m a great believer in learning by demonstration or even better, learning by doing.

I came across another explanatory video recently that I thought was too good to keep to myself. It covers a topic that was a complete mystery to me: Phase Locked Loops. We utilize them in almost every modern transmitter and receiver yet most people I have talked to view them as a black box that, fortunately, does its job well and usually without interruption.

The video below does a good job on opening the black box and showing just what makes phase locked loops … well, lock.

Heathkit’s first amateur transmitter – Heathkit AT-1

Heathkit’s first amateur transmitter – Heathkit AT-1

The Heathkit AT-1 represents the commercial embodiment of the simple Master Oscillator Power Amplifier (MOPA) transmitter using a crystal controlled 6AG7 oscillator plus a 6L6 final output tube.

Although it was possible to design and build a simpler transmitter, the goals of output power and stability could become mutually exclusive when trying to operate with only one tube. For a novice class license holder of 1951 the Heathkit AT-1 represented a solid performing rig that would be relatively easy to construct and operate.

The Novice remained the primary entry license until the Morse code requirement was eliminated for Technician licenses in 1990. On HF it permitted code transmissions only, with a maximum power of 75 watts, (input to the transmitter’s final amplifier stage) on limited segments of the 80, 40 and 15 meter bands.

| For $29.50 and the loan of a few tools you could get some use out of that new novice license |

The earlier MOPA circuit from the ARRL handbook of 1941 below shows a layout remarkably similar to the circuit of the AT-1 although it is designed for plug in coils rather than the band-switching arrangement of the later Heathkit transmitter.

| MOPA transmitter using a 6L6 and an 807 as the power amplifier (ARRL Handbook 1941) |

For a little added complexity MOPA transmitters generally offered better stability of frequency and keying waveform than single tube crystal controlled or self exited rigs. The straight forward design of the AT-1 should have looked familiar to novice class hams after studying the ARRL handbook or other radio publications.

|

| Heathkit AT-1 Circuit diagram showing band-switching arrangement and link coupled output |

Once the novice had upgraded his license the AT-1 could be expanded by the addition of the Heathkit VF-1 variable frequency oscillator to allow transmission on any frequency within the allowed band.

|

| The Heathkit VF-1 Variable Frequency Oscillator |

The VF-1 covered 160-80-40-20-15-11-10 meters and used an OA2 voltage regulator tube to provide a stable voltage for the oscillator. Ceramic coil forms, solid construction and high quality components were used to help increase stability.

|

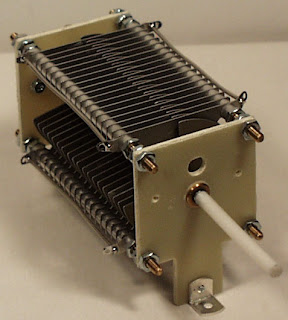

| The Heathkit AC-1 Antenna Coupler. Designed to attach to a single wire by the insulated post on the front panel. |

|

| Heathkit AC-1 Antenna Coupler circuit diagram |

Although Heathkit did not produce a AM modulator for the AC-1 there is provision for modulator connection on the rear panel. The earlier ARRL manuals have several suitable circuits for modulators that would work with the AC-1. Most functioned by driving a modulation transformer with the output from an audio power amplifier. The secondary of the modulation transformer would be carrying the DC plate supply for the power amplifier tube plus or minus the instantaneous voltage of the audio waveform. By changing the plate voltage to the final amplifier tube the radio frequency output would be controlled by the amplified audio frequency resulting in amplitude modulation.

South Texas Balloon Launch Team launches balloon aimed at China

South Texas Balloon Launch Team launches balloon aimed at China

My daughter and I made the short trip to the No Label Brewing Company in Katy TX to watch the South Texas Balloon Launch Team launch a helium balloon aimed at Nanjing China. Thanks to Tom AE5QB for letting us know about this event!

To track the balloon in real time go to : http://aprs.fi/?call=a%2FKT5TK-11&_s=mb

From the press release of the South Texas Balloon Launch Team:

The South Texas Balloon Launch Team is pleased to announce the upcoming launch of its twenty-eighth, helium-filled, unmanned balloon in twenty one years. The purpose of this flight is to establish a world record for distance by floating a balloon from Katy, Texas to Nanjing, China.

The balloon will be released at approximately 3 P.M. CST on Saturday, February 11, 2012. The site of the launch is at the western end of the No Label Brewery complex at 5373 First St., Katy Texas, near the old rice grain silos.

The public is invited to this free event, with a special invitation to science students and teachers. Free helium-filled balloons will be available to the first 100 students. Sorry, no pets allowed in the balloon area.

The balloon payload package weighs only about five ounces (150 grams) and contains a high altitude GPS tracking system and a VHF amateur radio transmitter. To conserve weight and battery life, no camera equipment will be on board. The maximum altitude is expected to be above 100,000 feet, with horizontal speeds between 100 and 150 MPH. The balloon size will increase from about five feet to about 39 feet at maximum elevation. Recovery of the payload package is not expected.

Individuals may follow the balloon’s progress on the Internet by logging onto APRS, filling in the “track callsign” field with “kt5tk-11”, and change the “show last” to 24 hours.

The South Texas Balloon Launch Team is composed of about twenty active amateur radio “Ham” operators from a variety of occupations who donate their time and expertise.

We appreciate the continued support by No Label Brewing Company for our amateur radio projects.