Posts Tagged ‘history’

The Wouff Hong

The Wouff Hong

One of the most interesting and unique artifacts from the early days of radio was not powered by batteries nor did it have any electronic components. I far as I can tell, Radio Shack never stocked it on their shelves and you can’t order it from Ham Radio Outlet.

From the 1969 ARRL “Radio Amateur’s Operating Manual”:

Every amateur should know and tremble at the history and origins of this fearsome instrument for punishment of amateurs who cultivate bad operating habits and who nourish and culture their meaner instincts on the air…

This is the Wouff Hong.

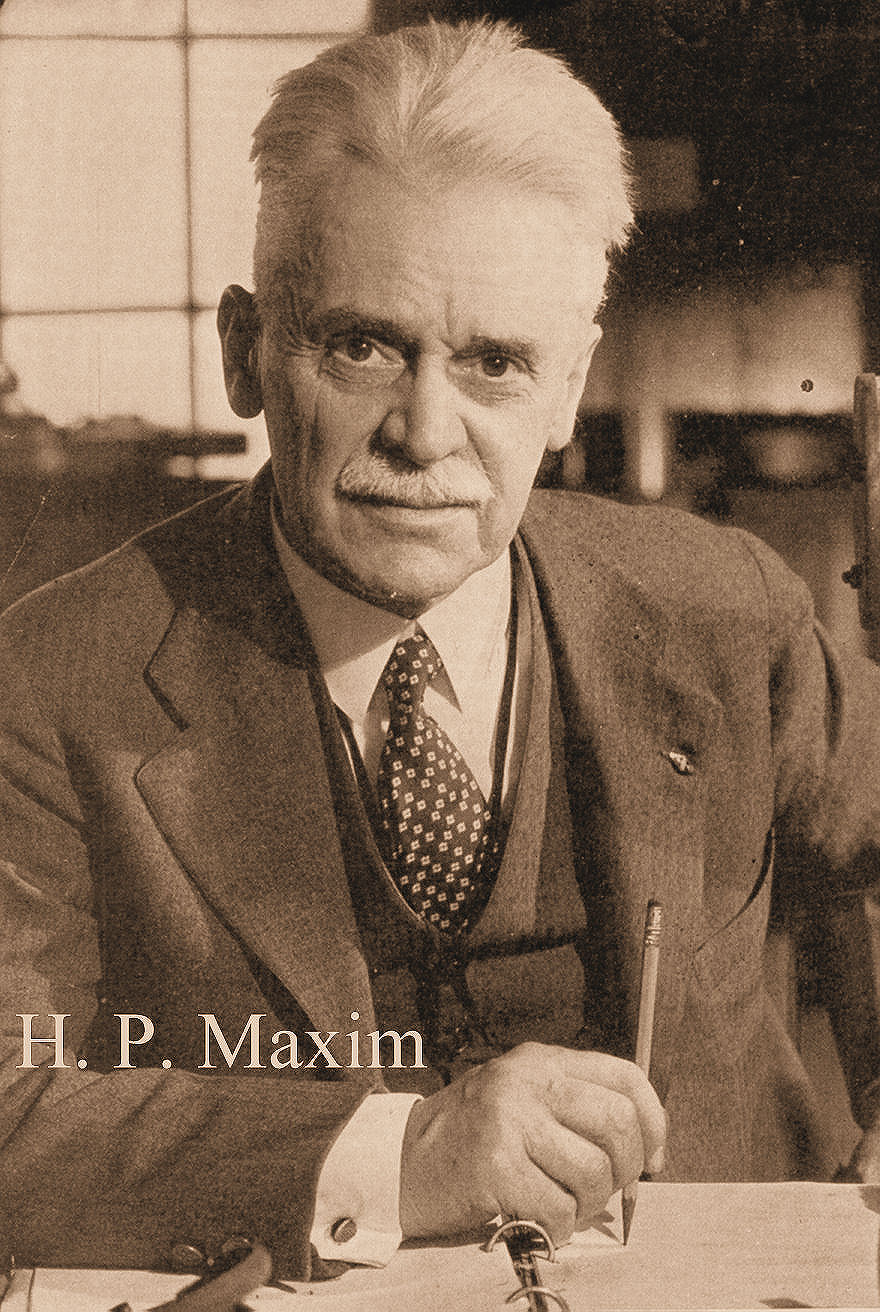

It was invented -or at any rate, discovered- by “The Old Man” himself, just as amateurs were getting back on the air after World War One. “The Old Man” (who later turned out to be Hiram Percy Maxim, W1AW, Co-founder and first president of ARRL) first heard the Wouff Hong described amid the howls and garble of QRM as he tuned across a band filled with signals which exemplified all the rotten operating practices then available to amateurs, considering the state of the art as they knew it. As amateur technology and ingenuity have advanced, we have discovered new and improved techniques of rotten operating, but we’re ahead of our story.

As The Old Man heard it, the Wouff Hong was being used on some hapless offender so effectively that he investigated. After further effort, “T.O.M.” was able to locate and identify a Wouff Hong. He wrote a number of QST articles about contemporary rotten operating practices and the use of the Wouff Hong to discipline the offenders.

Early in 1919, The Old Man wrote in QST “I am sending you a specimen of a real live Wouff Hong which came to light out here . . . Keep it in the editorial sanctum where you can lay hands on it quickly in an emergency.” The “specimen of a real live Wouff Hong” was presented to a meeting of the ARRL Board and QST reported later that “each face noticeably blanched when the awful Wouff Hong was . . . laid upon the table.” The Board voted that the Wouff Hong be framed and hung in the office of the Secretary of the League and there it remains to this day, a sobering influence on every visitor to League Headquarters who has ever swooshed a carrier across a crowded band.

The Old Man never prescribed the exact manner in which the Wouff Hong was to be used, but amateurs need only a little i

imagination to surmise how painful punishments were inflicted on those who stoop to liddish behavior on the air.

Read more about the Wouff Hong:

http://amfone.net/WouffHong/wouff.htm

http://www.netcore.us/wh/

http://everything2.com/title/Wouff+Hong

… and you can buy your very own miniature replica of the Wouff Hong in the form of a pin from ARRL. Now how cool is that?

Classic Radio Periodical Covers

Classic Radio Periodical Covers

Like others, I enjoy learning about the early history of radio. It gives me an idea of how far the hobby and technology has come as well as inspiring the imagination.

I found a great site, MagazineArt.org, which allows the viewer to peruse many of the covers from a variety of periodicals from the early days of the wireless.

Check out some of them here:

Popular Radio

Radio Age

Radio Craft

Radio News

The Wireless Age

Shortwave Craft

There’s a new radio hobby magazine in town!

There’s a new radio hobby magazine in town!

Recently, a number of hobby radio magazines have either retired, or have merged into a digital mix of several. Filling that void is the new The Spectrum Monitor, a creation of Ken Reitz KS4ZR, managing editor for Monitoring Times since 2012, features editor since 2009, columnist and feature writer for the MT magazine since 1988. Ken offers this digital, radio communications magazine monthly. The web site is at http://www.thespectrummonitor.com/

Ken, a former feature writer and columnist for Satellite Times, Satellite Entertainment Guide, Satellite Orbit magazine, Dish Entertainment Guide and Direct Guide, is also contributing editor on personal electronics for Consumers Digest (2007 to present). He is the author of the Kindle e-books “How to Listen to the World” and “Profiles in Amateur Radio.”

The Spectrum Monitor Writers’ Group consists of former columnists, editors and writers for Monitoring Times, a monthly print and electronic magazine which ceases publication with the December, 2013 issue. Below, in alphabetical order, are the columnists, their amateur radio call signs, the name of their column in The Spectrum Monitor, a brief bio and their websites:

Keith Baker KB1SF/VA3KSF, “Amateur Radio Satellites”

Past president and currently treasurer of the Radio Amateur Satellite Corporation (AMSAT). Freelance writer and photographer on amateur space telecommunications since 1993. Columnist and feature writer for Monitoring Times, The Canadian Amateur and the AMSAT Journal. Web site: www.kb1sf.com

Kevin O’Hern Carey WB2QMY, “The Longwave Zone”

Reporting on radio’s lower extremes, where wavelengths can be measured in miles, and extending up to the start of the AM broadcast band. Since 1991, editor of “Below 500 kHz” column forMonitoring Times. Author of Listening to Longwave (http://www.universal-radio.com/catalog/books/0024u.html). This link also includes information for ordering his CD, VLF RADIO!, a narrated tour of the longwave band from 0 to 530 kHz, with actual recordings of LW stations.

Mike Chace-Ortiz AB1TZ/G6DHU “Digital HF: Intercept and Analyze”

Author of the Monitoring Times “Digital Digest” column since 1997, which follows the habits of embassies, aid organizations, intelligence and military HF users, the digital data systems they use, and how to decode, breakdown and identify their traffic. Web site: www.chace-ortiz.org/umc

Marc Ellis N9EWJ, “Adventures in Radio Restoration”

Authored a regular monthly column about radio restoration and history since 1986. Originally writing for Gernsback Publications (Hands-On Electronics, Popular Electronics, Electronics Now), he moved his column to Monitoring Times in January 2000. Editor of two publications for the Antique Wireless Association (www.antiquewireless.org): The AWA Journal and the AWA Gateway. The latter is a free on-line magazine targeted at newcomers to the radio collecting and restoration hobbies.

Dan Farber ACØLW, “Antenna Connections”

Monitoring Times antenna columnist 2009-2013. Building ham and SWL antennas for over 40 years.

Tomas Hood NW7US, “Understanding Propagation”

Tomas first discovered radio propagation in the early 1970s as a shortwave listener and, as a member of the Army Signal Corps in 1985, honed his skills in communications, operating and training fellow soldiers. An amateur Extra Class operator, licensed since 1990, you’ll find Tomas on CW (see http://cw.hfradio.org ), digital, and voice modes on any of the HF bands. He is a contributing editor for CQ Amateur Radio (and the late Popular Communications, and CQ VHF magazines), and a contributor to an ARRL publication on QRP communications. He also wrote for Monitoring Times and runs the Space Weather and Radio Propagation Center at http://SunSpotWatch.com. Web site: http://nw7us.us/ Twitter: @NW7US YouTube: https://YouTube.com/NW7US

Kirk Kleinschmidt NTØZ, “Amateur Radio Insight”

Amateur radio operator since 1977 at age 15. Author of Stealth Amateur Radio. Former editor,ARRL Handbook, former QST magazine assistant managing editor, columnist and feature writer for several radio-related magazines, technical editor for Ham Radio for Dummies, wrote “On the Ham Bands” column and numerous feature articles for Monitoring Times since 2009. Web site: www.stealthamateur.com.

Cory Koral K2WV, “Aeronautical Monitoring”

Lifelong air-band monitor, a private pilot since 1968 and a commercial pilot licensee since 1983, amateur radio licensee for more than 40 years. Air-band feature writer for Monitoring Times since 2010.

Stan Nelson KB5VL, “Amateur Radio Astronomy”

Amateur radio operator since 1960. Retired after 40-plus years involved in mobile communications/electronics/computers/automation. Active in radio astronomy for over twenty years, specializing in meteor monitoring. Wrote the “Amateur Radio Astronomy” column for Monitoring Timessince 2010. A member of the Society of Amateur Radio Astronomers (SARA). Web site: www.RoswellMeteor.com.

Chris Parris, “Federal Wavelengths”

Broadcast television engineer, avid scanner and shortwave listener, freelance writer on federal radio communications since 2004, wrote the “Fed Files” column for Monitoring Times.http://thefedfiles.com http://mt-fedfiles.blogspot.com Twitter: @TheFedFiles

Doug Smith W9WI, “The Broadcast Tower”

Broadcast television engineer, casual cyclist and long distance reception enthusiast. “Broadcast Bandscan” columnist for Monitoring Times since 1991. Blog:http://americanbandscan.blogspot.com Web site: http://w9wi.com

Hugh Stegman NV6H, “Utility Planet”

Longtime DXer and writer on non-broadcast shortwave utility radio. Former “Utility World” columnist for Monitoring Times magazine for more than ten years. Web site: www.ominous-valve.com/uteworld.html Blog: http://mt-utility.blogspot.com/ Twitter: @UtilityPlanet YouTube: www.youtube.com/user/UtilityWorld

Dan Veeneman, “Scanning America”

Software developer and satellite communications engineer writing about scanners and public service radio reception for Monitoring Times for 17 years. Web site: www.signalharbor.com

Ron Walsh VE3GO, “Maritime Monitoring”

Retired career teacher, former president of the Canadian Amateur Radio Federation (now the Radio Amateurs of Canada), retired ship’s officer, licensed captain, “Boats” columnist and maritime feature writer for Monitoring Times for eight years. Avid photographer of ships and race cars.

Fred Waterer, “The Shortwave Listener”

Former “Programming Spotlight” columnist for Monitoring Times. Radio addict since 1969, freelance columnist since 1986. Fascinated by radio programming and history. Website: http://www.doghousecharlie.com/

Thomas Witherspoon K4SWL, “World of Shortwave Listening”

Founder and director of the charity Ears To Our World (http://earstoourworld.org), curator of the Shortwave Radio Archive http://shortwavearchive.com and actively blogs about shortwave radio on the SWLing Post (http://swling.com/blog). Former feature writer for Monitoring Times.

Bletchley Park, Enigma, and GB3RS

Bletchley Park, Enigma, and GB3RS

|

| Enigma (Photo: R. Holm) |

Bletchley Park, northwest of London (between Oxford and Cambridge), is one of the best known British sites from WW2. Its fame goes back to the breaking of the legendary Enigma cipher machine and its successor, the Lorenz cipher machine.

In order to perform this work a large effort in the development of early computers took place here. They include the mechanical Bombe for breaking the Enigma, and the valve-based Colossus for breaking the Lorenz.

The Bombe was reconstructed through a 13 year effort that resulted in an Engineering Heritage Award in 2009.

|

| The Bombe machine (Photo: R. Holm) |

Colossus was the world’s first electronic digital computer that was at all programmable. It was also finally reconstructed in 2007 despite most of the hardware and blueprints being destroyed after WW2.

I visited it with my oldest son who lives in Cambridge, and it was a fascinating place that made me want to learn more about the work done at Bletchley Park and in particular one of the founders of computation, the brilliant Alan Turing, who was treated so badly after the war.

|

| From left: Henry Ehm (M0ZAE), Peter Davies (M0PJD), and Alan Goold (2E0GLD) on duty 5. April 2014 |

I was also impressed by the National Radio Centre run by the RSGB, callsign GB3RS, with its informative and well laid out exhibition and demonstrations.

They are able to keep it staffed for four days a week based on volunteers, and I really appreciated the hospitality and friendliness of the radio amateurs I met there.

If you ever come to London you should really try to visit this place. It is only a 36 minute train ride from London Euston station.

PEARL HARBOR: PATTON VS THE SIGNAL CORPS

PEARL HARBOR: PATTON VS THE SIGNAL CORPS

“Getting the Message Through: A Branch History of the U.S. Army Signal Corps” by Rebecca Robbins Raines

CENTER OF MILITARY HISTORY, UNITED STATES ARMY, WASHINGTON, D.C., 1996 (pgs 242-244)

During 1940 President Roosevelt had transferred the Pacific Fleet from bases on the West Coast of the United States to Pearl Harbor on the Hawaiian island of Oahu, hoping that its presence might act as a deterrent upon Japanese ambitions. Yet the move also made the fleet more vulnerable. Despite Oahu’s strategic importance, the air warning system on the island had not become fully operational by December 1941. The Signal Corps had provided SCR-270 and 271 radar sets earlier in the year, but the construction of fixed sites had been delayed, and radar protection was limited to six mobile stations operating on a part-time basis to test the equipment and train the crews. Though aware of the dangers of war, the Army and Navy commanders on Oahu, Lt. Gen. Walter C. Short and Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, did not anticipate that Pearl Harbor would be the target; a Japanese strike against American bases in the Philippines appeared more probable. In Hawaii, sabotage and subversive acts by Japanese inhabitants seemed to pose more immediate threats, and precautions were taken. The Japanese-American population of Hawaii proved, however, to be overwhelmingly loyal to the United States.

Because the Signal Corps’ plans to modernize its strategic communications during the previous decade had been stymied, the Army had only a limited ability to communicate with the garrison in Hawaii. In 1930 the Corps had moved WAR’s transmitter to Fort Myer, Virginia, and had constructed a building to house its new, high-frequency equipment. Four years later it added a new diamond antenna, which enabled faster transmission. But in 1939, when the Corps wished to further expand its facilities at Fort Myer to include a rhombic antenna for point-to-point communication with Seattle, it ran into difficulty. The post commander, Col. George S. Patton, Jr., objected to the Signal Corps’ plans. The new antenna would encroach upon the turf he used as a polo field and the radio towers would obstruct the view. Patton held his ground and prevented the Signal Corps from installing the new equipment. At the same time, the Navy was about to abandon its Arlington radio station located adjacent to Fort Myer and offered it to the Army. Patton, wishing instead to use the Navy’s buildings to house his enlisted personnel, opposed the station’s transfer. As a result of the controversy, the Navy withdrew its offer and the Signal Corps lost the opportunity to improve its facilities.

Though a seemingly minor bureaucratic battle, the situation had serious consequences two years later. Early in the afternoon of 6 December 1941, the Signal Intelligence Service began receiving a long dispatch in fourteen parts from Tokyo addressed to the Japanese embassy in Washington. The Japanese deliberately delayed sending the final portion of the message until the next day, in which they announced that the Japanese government would sever diplomatic relations with the United States effective at one o’clock that afternoon. At that hour, it would be early morning in Pearl Harbor.

Upon receiving the decoded message on the morning of 7 December, Chief of Staff Marshall recognized its importance. Although he could have called Short directly, Marshall did not do so because the scrambler telephone was not considered secure. Instead, he decided to send a written message through the War Department Message Center. Unfortunately, the center’s radio encountered heavy static and could not get through to Honolulu. Expanded facilities at Fort Myer could perhaps have eliminated this problem. The signal officer on duty, Lt. Col. Edward F French, therefore sent the message via commercial telegraph to San Francisco, where it was relayed by radio to the RCA office in Honolulu. That office had installed a teletype connection with Fort Shafter, but the teletypewriter was not yet functional. An RCA messenger was carrying the news to Fort Shafter by motorcycle when Japanese bombs began falling; a huge traffic jam developed because of the attack, and General Short did not receive the message until that afternoon.

PEARL HARBOR: PATTON VS THE SIGNAL CORPS

PEARL HARBOR: PATTON VS THE SIGNAL CORPS

“Getting the Message Through: A Branch History of the U.S. Army Signal Corps” by Rebecca Robbins Raines

CENTER OF MILITARY HISTORY, UNITED STATES ARMY, WASHINGTON, D.C., 1996 (pgs 242-244)

During 1940 President Roosevelt had transferred the Pacific Fleet from bases on the West Coast of the United States to Pearl Harbor on the Hawaiian island of Oahu, hoping that its presence might act as a deterrent upon Japanese ambitions. Yet the move also made the fleet more vulnerable. Despite Oahu’s strategic importance, the air warning system on the island had not become fully operational by December 1941. The Signal Corps had provided SCR-270 and 271 radar sets earlier in the year, but the construction of fixed sites had been delayed, and radar protection was limited to six mobile stations operating on a part-time basis to test the equipment and train the crews. Though aware of the dangers of war, the Army and Navy commanders on Oahu, Lt. Gen. Walter C. Short and Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, did not anticipate that Pearl Harbor would be the target; a Japanese strike against American bases in the Philippines appeared more probable. In Hawaii, sabotage and subversive acts by Japanese inhabitants seemed to pose more immediate threats, and precautions were taken. The Japanese-American population of Hawaii proved, however, to be overwhelmingly loyal to the United States.

Because the Signal Corps’ plans to modernize its strategic communications during the previous decade had been stymied, the Army had only a limited ability to communicate with the garrison in Hawaii. In 1930 the Corps had moved WAR’s transmitter to Fort Myer, Virginia, and had constructed a building to house its new, high-frequency equipment. Four years later it added a new diamond antenna, which enabled faster transmission. But in 1939, when the Corps wished to further expand its facilities at Fort Myer to include a rhombic antenna for point-to-point communication with Seattle, it ran into difficulty. The post commander, Col. George S. Patton, Jr., objected to the Signal Corps’ plans. The new antenna would encroach upon the turf he used as a polo field and the radio towers would obstruct the view. Patton held his ground and prevented the Signal Corps from installing the new equipment. At the same time, the Navy was about to abandon its Arlington radio station located adjacent to Fort Myer and offered it to the Army. Patton, wishing instead to use the Navy’s buildings to house his enlisted personnel, opposed the station’s transfer. As a result of the controversy, the Navy withdrew its offer and the Signal Corps lost the opportunity to improve its facilities.

Though a seemingly minor bureaucratic battle, the situation had serious consequences two years later. Early in the afternoon of 6 December 1941, the Signal Intelligence Service began receiving a long dispatch in fourteen parts from Tokyo addressed to the Japanese embassy in Washington. The Japanese deliberately delayed sending the final portion of the message until the next day, in which they announced that the Japanese government would sever diplomatic relations with the United States effective at one o’clock that afternoon. At that hour, it would be early morning in Pearl Harbor.

Upon receiving the decoded message on the morning of 7 December, Chief of Staff Marshall recognized its importance. Although he could have called Short directly, Marshall did not do so because the scrambler telephone was not considered secure. Instead, he decided to send a written message through the War Department Message Center. Unfortunately, the center’s radio encountered heavy static and could not get through to Honolulu. Expanded facilities at Fort Myer could perhaps have eliminated this problem. The signal officer on duty, Lt. Col. Edward F French, therefore sent the message via commercial telegraph to San Francisco, where it was relayed by radio to the RCA office in Honolulu. That office had installed a teletype connection with Fort Shafter, but the teletypewriter was not yet functional. An RCA messenger was carrying the news to Fort Shafter by motorcycle when Japanese bombs began falling; a huge traffic jam developed because of the attack, and General Short did not receive the message until that afternoon.