LHS Episode #272: The Weekender XXIV

LHS Episode #272: The Weekender XXIV

Good grief! It's the latest edition of the Weekender! In this episode, the hosts put together a list of amateur radio contests and special events, upcoming open source conferences and a hefty does of hedonism that blends together and goes down like a luxurious sippin' whiskey. Thank you for tuning in and we hope you have an amazing upcoming fortnight.

73 de The LHS Crew

Russ Woodman, K5TUX, co-hosts the Linux in the Ham Shack podcast which is available for download in both MP3 and OGG audio format. Contact him at [email protected].

SOTA News: Joyce/K0JJW Is Half a Goat

SOTA News: Joyce/K0JJW Is Half a Goat

Recently, my SOTA Activating Partner and Spousal Unit Joyce/K0JJW racked up more than 500 activating points for Summits On The Air (SOTA). This is halfway towards the coveted Mountain Goat award, so naturally this is referred to as Half Mountain Goat. Steve/WG0AT noticed this achievement and created this certificate for her.

She has activated 108 summits in 13 different associations (including HB Switzerland). All radio contacts have been on the VHF/UHF bands. She really likes it when another woman gets on the air with her, which she calls F2F (Female-to-Female) radio contact.

Congratulations, Joyce!

73 Bob K0NR

The post SOTA News: Joyce/K0JJW Is Half a Goat appeared first on The KØNR Radio Site.

Bob Witte, KØNR, is a regular contributor to AmateurRadio.com and writes from Colorado, USA. Contact him at [email protected].

A Blog a day: The Daily Antenna

A Blog a day: The Daily Antenna

The maestro of the Ham Video VK3YE , writer of a growing Amateur radio book collection along with his superb website to support his hobby vk3ye.com Has done it again, and now come up with a new challenge a new daily Blog called The Daily Antenna

The idea is to produce One blog per day on antennas, accessories and related topics.

I don't know how Peter finds the energy to fit it all in, but I certainly will be dropping in and reading from time to time and wish him well with his new venture

I will also drop the link into My Blog list on the right handside, because I know it will be a very valuable source of material.

Steve, G1KQH, is a regular contributor to AmateurRadio.com and writes from England. Contact him at [email protected].

LHS Episode #271: The Discord Accord

LHS Episode #271: The Discord Accord

Welcome to Episode 271 of Linux in the Ham Shack. In this week's episode, the hosts discuss ARISS Phase 2, the Peanut Android app for D-STAR and DMR linking, a geostationary satellite from Qatar, open source software in the public sector, a new open-source color management tool, Linux distributions for ham radio and much more. Thank you to everyone for listening and don't forget our Hamvention 2019 fundraiser!

73 de The LHS Crew

Russ Woodman, K5TUX, co-hosts the Linux in the Ham Shack podcast which is available for download in both MP3 and OGG audio format. Contact him at [email protected].

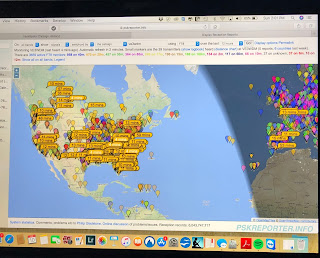

FT8 on 20m this afternoon

FT8 on 20m this afternoon

Mike Weir, VE9KK, is a regular contributor to AmateurRadio.com and writes from New Brunswick, Canada. Contact him at [email protected].

Mr. Carlson’s Lab – A YouTube Treasure

Mr. Carlson’s Lab – A YouTube Treasure

I recently watched two superb YouTube videos. The first described exactly how to determine the 'shielded' side of a fixed capacitor and the importance of knowing this information.

As you have probably noticed, most modern fixed capacitors no longer indicate the 'grounded' end or the lead going to the internal shielding. At one time, the capacitor's polarity was commonly marked with a band on one end but this is no longer the case ... even though one side is indeed still the shielded side. Depending on exactly what part of the circuit your fixed capacitor is being used in, connecting it in the reverse direction (shield going to signal side), can introduce hum, RF pickup, instability and generally result in poorer capacitor / circuit performance ... and all it takes to determine which lead is which is an oscilloscope!

The second video I viewed shows the process used to resurrect a Yaesu FT-1000MP in truly terrible condition. In a very professional step-by-step process the video shows the logical and systematic approach at making the radio better than new.

Both videos are done by a truly gifted engineer, Paul Carlson, VE7ZWZ, and are exceptionally well done ... the quality one would expect to have to pay for rather than freely view on YouTube.

If you visit Paul's YouTube channel, you'll find a host of other radio and audio-related videos and I guarantee that you will learn something of value ... and probably hang around to watch several more. They are really well done.

Steve McDonald, VE7SL, is a regular contributor to AmateurRadio.com and writes from British Columbia, Canada. Contact him at [email protected].

The Myth of VHF Line-Of-Sight

The Myth of VHF Line-Of-Sight

When we teach our Technician License class, we normally differentiate between HF and VHF propagation by saying that HF often exhibits skywave propagation but VHF is normally line-of-sight. For the beginner to ham radio, this is a reasonable model for understanding the basics of radio propagation. As George E. P. Box said, “All models are wrong, but some are useful.”

In recent years, I’ve come to realize the limitations of this model and how it causes radio hams to miss out on what’s possible on the VHF and higher bands.

Exotic Propagation Modes

First, let me acknowledge and set aside some of the more exotic propagation modes used on the VHF and higher bands. Sporadic-e propagation allows long distance communication by refracting signals off the e-layer of the ionosphere. This is very common on the 6-meter band and less so on the 2-meter band. I like to think of this as the VHF bands trying to imitate HF. Tropospheric ducting supports long distance VHF communication when ducts form between air masses of different temperatures and humidities. Auroral propagation reflects the radio signal off the auroral ionization that sometimes occurs in the polar regions. Meteor scatter reflects signals off the ionizing trail of meteors entering the earth’s atmosphere. Earth-Moon-Earth (EME) operation bounces VHF and UHF signals off the moon to communicate with other locations on earth. These are all interesting and useful propagation mechanisms for VHF and higher but not the focus of this article.

Improved Line-of-Sight Model

Now let’s take a look at more “normal” VHF propagation that occurs on a daily basis, starting with the simple line-of-sight propagation model. The usual description of line-of-sight VHF is that the radio waves travel a bit further than the optical horizon (say 15% more) . Let’s refer to this as the Line-of-Sight (LOS) region where signals are usually direct and strong. What is often overlooked is that beyond the radio horizon, these signals continue to propagate but with reduced signal level. Let’s call this the Non-Line-of-Sight (NLOS) region. The key point is that the radio waves do not abruptly stop at the edge of the LOS region…they keep going into the NLOS region but with reduced signal strength. Now I will admit that this is still a rather simplistic model. Perhaps too simplistic. I’m sure we could use computer modeling to be more descriptive and precise, but this model will be good enough for this article. All models are wrong, but some are useful.

Now let’s take a look at more “normal” VHF propagation that occurs on a daily basis, starting with the simple line-of-sight propagation model. The usual description of line-of-sight VHF is that the radio waves travel a bit further than the optical horizon (say 15% more) . Let’s refer to this as the Line-of-Sight (LOS) region where signals are usually direct and strong. What is often overlooked is that beyond the radio horizon, these signals continue to propagate but with reduced signal level. Let’s call this the Non-Line-of-Sight (NLOS) region. The key point is that the radio waves do not abruptly stop at the edge of the LOS region…they keep going into the NLOS region but with reduced signal strength. Now I will admit that this is still a rather simplistic model. Perhaps too simplistic. I’m sure we could use computer modeling to be more descriptive and precise, but this model will be good enough for this article. All models are wrong, but some are useful.

WORKING the LOS and NLOS Regions

Let’s apply the model for Summits On The Air (SOTA) VHF activations. If we are only interested in working the LOS region, we won’t need much of a radio. Even a handheld transceiver with a rubber duck antenna can probably make contacts in the LOS region. It’s still worth upgrading the rubber duck antenna to something that actually radiates to improve our signal (such as a half-wave antenna). We may pick up some radio contacts in the NLOS region as well but our success will be limited.

To improve our results in the NLOS zone, we need to increase our signal strength. We are working on the margin, so every additional dB can make enough difference to go from “no contact” to “in the log.” Think about another radio operator sitting in the NLOS zone but not quite able to hear your signal. Your signal is just a bit too weak and is just below the noise floor of the operator’s receiver. Now imagine that you improve your signal strength by 3 dB, which is just enough to get above the noise and be a readable signal. You’ve just gone from “not readable” to “just readable” with only a few dB improvement.

What can we do to improve our signal levels? The first thing to try is improving the antenna, which helps you on both transmit and receive. I already mentioned the need to ditch the rubber duck on your HT. My measurements indicate that a half-wave vertical is about 8 dB better than a typical rubber duck. This is only an estimate…performance of rubber duck antennas vary greatly. A small yagi (3-element Arrow II yagi) can add another 6 dB improvement over the half-wave antenna, which means a yagi has about a 14 dB advantage over a rubber duck.

On the other hand, if you believe that your VHF radio is only Line-of-Sight, then there is no reason to work on increasing its signal level. The radio wave is going to travel to anything within the radio horizon and then it will magically stop. This is the myth that we need to break.

More Power

When doing SOTA activations, I noticed that I was able to hear some stations quite well but they were having trouble hearing me. Now why would this be? Over time, I started to realize these stations were typically home or mobile stations running 40 or 50 watts of output. This created an imbalance between the radiated signal from my 5W handheld and their 50 watts. In decibels, this difference is 10 dB. Within the LOS region, this probably is not going to matter because signals are strong anyway. But when trying to make more distant radio contracts into the NLOS zone, it definitely makes a difference. So I traded my HT for a mini-mobile transceiver running 25W. See the complete story in Chapter: More Power For VHF SOTA.

Weak Signal VHF

Of course, this is nothing new for serious weak-signal VHF enthusiasts. They operate in the NLOS region all of the time, squeezing out distance QSOs using CW, SSB and the WSJT modes. They generally use large directional antennas, low noise preamps and RF power amplifiers to improve their station’s performance. They know that a dB here and a dB there adds up to bigger signals, longer distances and more radio contacts. A well-equipped weak-signal VHF station in “flatland geography” can work over 250 miles on a regular basis…no exotic propagation required.

Now you might think that FM behaves differently, because of the threshold effect. When FM signals get weak, they fade into the noise quickly…a rather steep cliff compared to SSB which fades linearly. FM has poor weak-signal performance AND it fades quickly with decreasing signal strength. This is why it is not the favored modulation for serious VHF work. But the same principle applies: if we can boost our signal strength by a few dB, it can make the difference between making the radio contact or not.

So VHF is not limited to line-of-sight propagation…the signals go much further. But they do tend to be weak in signal strength so we need to optimize everything under our control to maximize our range.

73, Bob K0NR

The post The Myth of VHF Line-Of-Sight appeared first on The KØNR Radio Site.

Bob Witte, KØNR, is a regular contributor to AmateurRadio.com and writes from Colorado, USA. Contact him at [email protected].